African pneumonia vaccination delays kill thousands needlessly 2023

Delays in rolling out a vaccine against childhood pneumonia in four of the world’s poorest countries have been blamed for thousands of unnecessary fatalities.

South Sudan, Somalia, Guinea and Chad are four of the last African nations without the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), one of the most effective tools against pneumonia in children.

Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease suggest 40,000 children perished from the illness in the four countries in 2019, which are all off track to meet UN targets to reduce deaths of children under five by 2030.

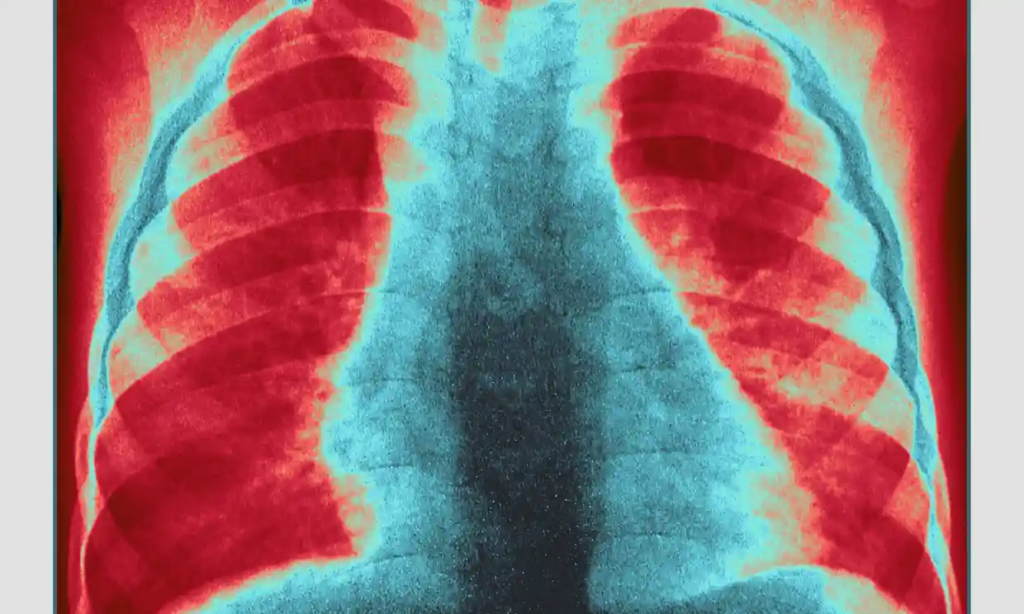

Childhood pneumonia is the largest infectious killer of children worldwide, claiming 700,000 lives annually. It is a disease of poverty, with almost all fatalities occurring in low- and middle-income countries, and most of them are preventable.

“It’s unfair that this vaccine is not yet available because every child has a right to survive and thrive,” said Dr Ubah Farah, an adviser to Somalia’s health ministry.

She said pneumonia was a “big killer” in the country, and noted that the Covid vaccine had been rolled out rapidly by comparison. “Why can’t we do the same for children?” she said. “It’s double standards.”

Prof Fiona Russell, a vaccinologist from the University of Melbourne and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, termed the delays “a failure”.

“How many thousands of children have died while waiting to get this vaccine?”

The PCV targets the primary bacterial cause of pneumonia and was introduced in the US in 2000 and to South Africa in 2009. Most African states now have the vaccine, and studies indicate that hospitalisations and deaths fall significantly after rollout, including in Rwanda, South Africa and Kenya.

At the second Global Forum on Childhood Pneumonia, held in Madrid last week, delegates from South Sudan, Somalia, Guinea and Chad announced plans to roll out the vaccine in 2024 with the assistance of Gavi, a global health alliance that shares the cost that countries pay for vaccines.

The four countries first intended to introduce the vaccine three years ago but struggled to meet Gavi’s co-financing requirements. Gavi pays for the majority of the initial implementation, but countries are required to contribute, with a plan to cover all costs in the future.

Gavi was exhorted to be more flexible with its payment requirements.

The rollouts were also delayed by Covid, and Guinea encountered two outbreaks of Ebola, which hit the country and its health system hard, while South Sudan and Somalia are in the grip of a humanitarian crises caused by conflict and drought.

South Sudan and Somalia, as fragile states confronting massive humanitarian crises, will no longer be required to pay for the introduction of vaccines, Gavi announced at the forum.

“This is an uprising. We have never waived [the cost] for new [vaccine] programs before,” said Gavi’s senior programme manager, Veronica Denti. “The guiding principle of Gavi is that we want [governments] to find a way to pay for it, because that’s how you build sustainability.”

Russell stated, “In these troubled and impoverished nations, the government has the desire, but they cannot locate the additional funds. It will be much more difficult for them to achieve their Sustainable Development Goal objective [to reduce child mortality by 2030] if they do not have access to the vaccine.