7 Kidney Cancer Myths Busted 2023

Kidney cancer may be America’s least-known prevalent malignancy. American Cancer Society estimates 81,800 new cases this year. In 2022, it was the seventh most prevalent cancer, surpassing leukemia and thyroid cancer. Dr. Alice C. Fan, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of oncology at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif., says patients commonly say, “I didn’t even know you could get kidney cancer.”

Both sides of humans have fist-sized kidneys shaped like kidney beans. They’re backward below your rib cage. The kidney’s million or more microscopic filters cleanse 200 quarts of blood daily, eliminating toxins, extra minerals, and water to form urine. The kidneys release hormones that regulate blood pressure, stimulate bone marrow to create red blood cells, and convert Vitamin D from diet or sun exposure into a form the body can use.

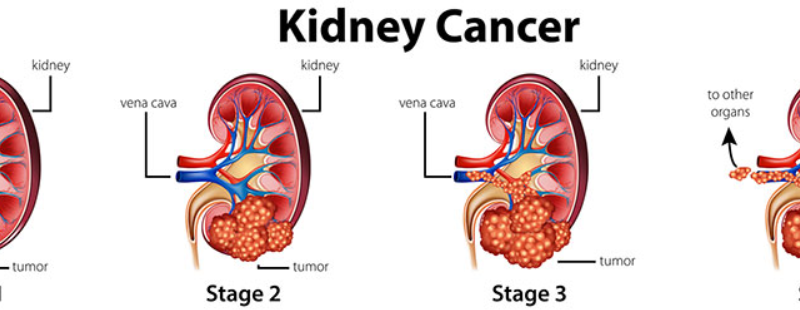

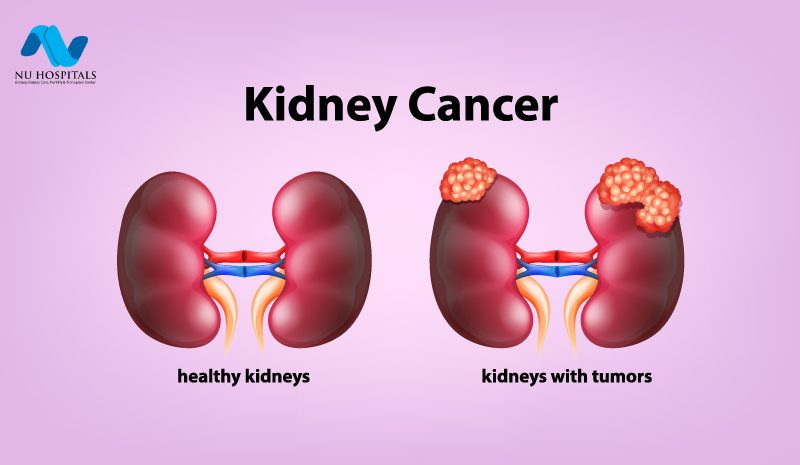

Tiny filters cause most kidney cancer. Usually present in the kidney. Its spread to other sections of the body had a poor prognosis until recently. Over the previous two decades, treatment has improved. Experts like Fan meet these kidney cancer fallacies.

Myth: Kidney cancer has only one type.

Fact: Cancers are named for their organs. But those broad categories hide tumors’ variety. Even kidney cancer. Dr. Chung-Han Lee, a genitourinary oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, says clear cell renal cell carcinoma affects 70% to 75% of kidney cancer patients. Non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma, which includes papillary, renal medullary, and chromophobe instances, is caused by a variety of cells. Fan adds that aggressive “sarcomatoid” subtypes complicate matters.

Lee says the pathologist classifies under the microscope. That will determine treatment options. Patients should request confirmation of pathology results or a second opinion if possible.

Myth: Everyone gets kidney cancer.

Fact : Like most malignancies, it disproportionately affects elderly people: The ACS says most persons are diagnosed between 65 and 74. The ACS reports that men have a 2% lifetime risk of the condition, while women have 1%. Gender inequality is unknown. race matters. Lee thinks blood pressure, obesity, and genetics may make black Americans more prone to develop rare kidney cancer subtypes than white Americans.

Myth: Most kidney cancers are avoidable.

Fact: “I always get asked why I got kidney cancer.” Dr. Sangeeta Goswami, assistant professor of genitourinary medical oncology and immunology at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, explains. Rarely inherited. According to the National Cancer Institute, 5% to 8% of kidney cancer patients have a genetic condition that increases cancer risk. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, for instance, produces multiple organ cancers and increases kidney and pancreatic cancer risk.

Modifiable risk variables are not strongly linked. Lee thinks smoking doubles kidney cancer risk. Smokers are 15–30 times more likely to have lung cancer than nonsmokers, according to the CDC. Lee also notes a slight link to obesity and high blood pressure. Tobacco, alcohol, and obesity are connected to numerous diseases, including cancer, therefore it’s best to avoid them. Kidney cancer correlations are modest. Kidney cancer is usually a fluke. Lee calls it devastating. “People can do everything right, go to the doctor regularly, and get that call.”

Myth: Kidney cancer screenings are necessary.

Fact: There is no kidney cancer screening test like the mammography or PSA. Imaging tests are used to monitor genetically high-risk individuals, while average-risk individuals cannot.

Blood in the urine or back discomfort used to be the main indicators of tumors. Advanced patients may feel exhausted. Report those symptoms to your doctor. Don’t worry—blood in the urine can indicate several things, including a urinary tract infection. Today, doctors find kidney cancer while seeking for something else. “People are being scanned for something else—maybe they were in a car accident—and kidney cancer is found,” adds Goswami.

Some of those tumors will be small or slow-growing, but around a third will have gone beyond the kidneys when discovered. Detecting kidney cancer early is the goal. Fan says it’s difficult. Many screening tests look for “a positive signal—a mutation or something in the blood,” she explains. However, kidney cancer commonly loses chromosomes and tumor suppressor genes. Fan says it’s hard to spot a missing chromosome in blood from normal cells. “You’re not looking for a needle in a haystack, but for its loss. That’s harder.”

Fan and her colleagues are searching for kidney cancer using autoantibodies. “If the immune system is important for kidney cancer, it might remember if it’s seen and gotten rid of a kidney cancer cell,” she says. Platelets are being studied as reporters since their RNA signature changes with their environment.

The Myth: Stage 1-3 kidney cancer treatment usually involves surgery and chemotherapy.

Facts: Half right. Most stage 1–3 cancer patients undergo surgery first. (Some small, slow-growing early-stage tumors may be watched or treated non-surgically.) Most people can function with one kidney if both must be removed.

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma is resistant to chemotherapy. Goswami says post-surgery active surveillance—regular scans to check for recurrence—is typical. She adds doctors may use newer medications (more on those later) after surgery in early-stage disease patients at high risk of recurrence, but studies have not shown that they lengthen life. She advises discussing the advantages and downsides of post-surgery medicines.

Myth: Only kidneys get kidney cancer.

Fact: Kidney cancer spreads to other organs but remains kidney cancer. Lee calls cancer a weed. “It doesn’t change when it’s in the wrong place.” If the cancer metastasizes to the lung, brain, or adrenal system, it will be treated like kidney cancer, not like cancers from those organs.

Myth: Metastatic kidney cancer has no effective treatments.

Fact: Until around 20 years ago. Stage 4 disease—which has expanded beyond the kidneys and is harder to treat—affects about one-third of individuals. Some early-stage cases spread after surgery. “Stage 4 used to mean months to live,” Fan recalls.

Two medications altered that. The first targeted medicines used the knowledge that kidney cancer cells lose their ability to sense oxygen and generate many more blood vessels to grow and thrive, adds Fan. Angiogenesis inhibitors, initially licensed for kidney cancer in 2005, prevent blood vessel development. Those medications increased stage 4 median survival from less than a year to two and a half years.

Recently, kidney cancer medications that use the immune system to identify and target tumor cells have been approved. Checkpoint inhibitors target a protein on the body’s T cells that keeps the immune system from overreacting and causing health issues. Stage 4 patients can start these therapy without trying others. Lee notes that these immunotherapy medications have fewer adverse effects than older ones.

They’re also utilized together and with targeted therapy, which may be better than single medications or classes. Lee says immunotherapies extend life for half of the patients. Immunotherapy only lasts for one-third of renal cell carcinoma patients.

Fan states that in kidney cancer, PD-L1 expression in tumor cells does not always predict a greater immunotherapy response. (Some renal cell carcinomas respond without significant PD-L1 protein.) Immunosuppressed patients respond less. She says some research is looking at the microbiome—gut bacteria—and immunotherapy.

“It’s still baby steps, but we have made tremendous progress in the past 10 years where we could significantly prolong the lives of patients with advanced kidney cancer,” Goswami adds.